5.3 Assessing microbial risk

The likelihood that a drinking water source may lead to disease can be evaluated using two different approaches:

Epidemiology and Surveillance both investigate patterns in cases of disease and can be used to assess any statistically causal link between drinking water and disease. Epidemiology refers to specific investigations exploring statistical associations between cause and effect. Surveillance is the ongoing activity of monitoring cases of disease in the population. Existing disease surveillance systems are designed for early detection of waterborne disease outbreaks. However, even relatively elevated levels of waterborne disease may not be detected by routine disease surveillance in Australia. This is particularly the case in small populations or where only a small proportion of a larger community are exposed (Gibney et al. 2014).

Risk assessment estimates the probability of disease based on the:

occurrence of hazards in the catchment

likelihood of exposure

likelihood of subsequent human disease.

Risk assessment can be undertaken at different levels of detail and rigour depending on the purpose of the work (e.g. meeting regulatory requirements). This can include simple categorical identification of hazards and risks through to qualitative risk assessment and quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) (Deere and Davison 2005; WHO 2016).

Qualitative risk assessment rates the risks using categories of likelihood and consequence (see Section 3.2.3). The approach is good for screening large numbers of risks rapidly (as detailed in Element 2 of the Framework, see Section 3.2.3).

Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment (QMRA) involves quantifying each component of the exposure pathway, together with the estimated health outcome. The outcome of a QMRA is a quantitative assessment of risk and is most applicable for answering quantitative questions such as: “What is safe?” and “How much treatment is required to achieve safety?”

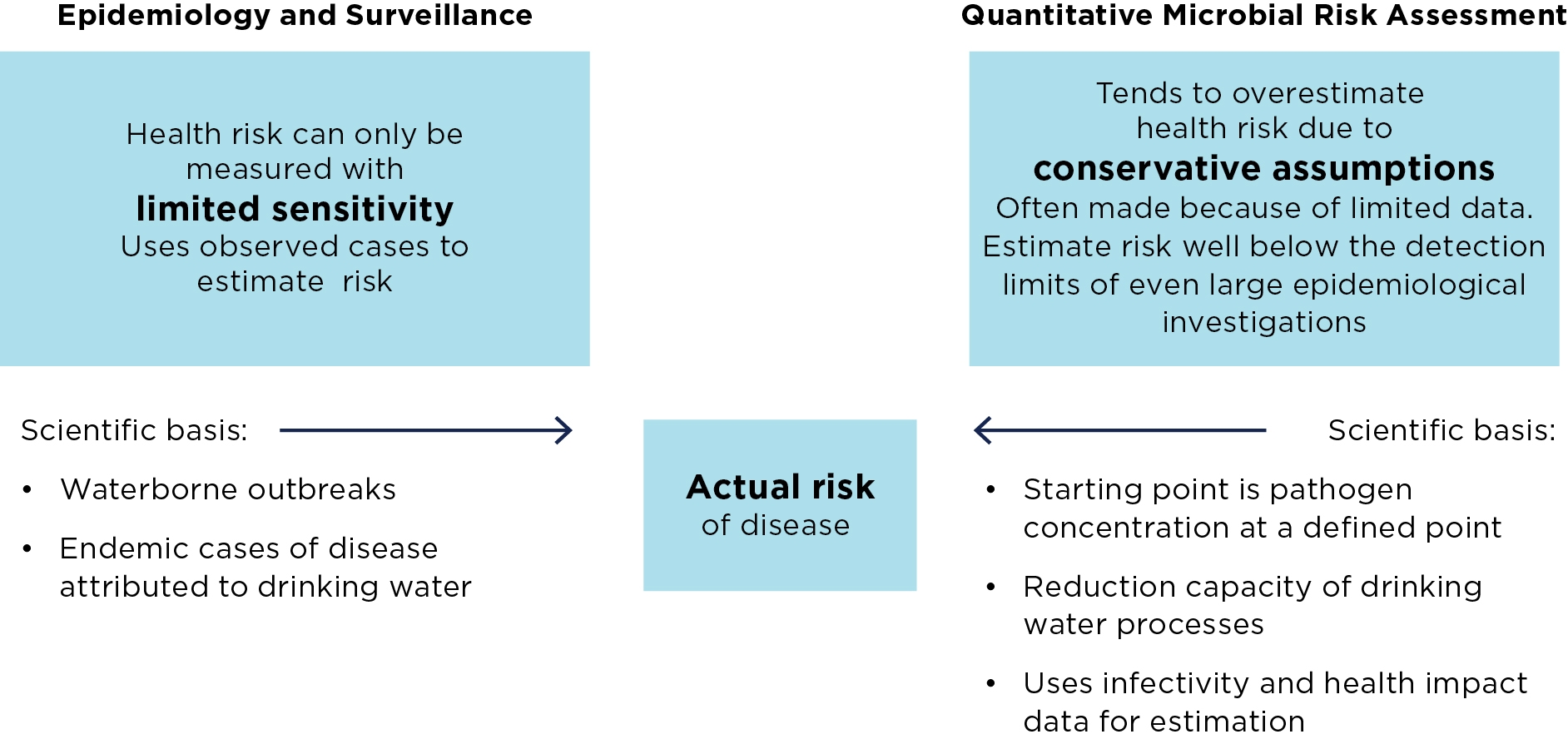

The different approaches and data needs of epidemiology and risk assessment (QMRA) are illustrated in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 QMRA and epidemiological approaches to characterising risks from drinking water sources

Epidemiology and surveillance are limited in their ability to detect waterborne disease given that:

water contamination is often transient and gone long before the first cases of disease are identified

often only a small subset of cases are identified due to under-reporting (although this can be overcome in a specifically designed epidemiological study).

For example, outbreaks of gastroenteritis may be difficult for health authorities to recognise because illness is often mild and self-limiting. In addition, people do not usually seek medical attention or have a faecal specimen taken and most faecal specimens do not yield a pathogen (Frost et al. 1996; Gibney et al. 2014).

Given the limitations of disease surveillance mechanisms to measure endemic disease, an alternative approach is needed to estimate and manage endemic disease burdens to ensure that water is safe. QMRA investigates the likelihood of disease along a risk pathway from the point at which pathogen concentration is quantified (e.g. in a water source) to the receptor (e.g. a consumer of drinking water). Based on scientific evidence from environmental microbiology and controlled human feeding trial datasets, QMRA aims to estimate exposure and the resulting health impact (WHO 2016). QMRA is a logical framework that brings together a diverse range of important scientific evidence. However, the actual health impact is estimated (not observed) and is typically conservative.

QMRA approaches have been used by several organisations internationally. The WHO, Health Canada and the United States Environment Protection Association (USEPA) support defining water safety targets below the threshold of epidemiological methods. The methodology applied for the Guidelines is based on the approach used by WHO (WHO 2016).